Telling of the Bees

2019—Present InternationalWhat we have, we owe to bees. Among the most prolific pollinators on the planet, bees helped create and maintain the biodiverse ecosystems that made it possible for humanity to take root and grow. Over millions of years, our shared evolution has grown increasingly intertwined. And today, human activity is impacting wild and domesticated bee populations in unprecedented ways. Due to the integral role bees play in supporting the ecosystems we depend on, this ongoing relationship affects us all: bee, human, and otherwise.

Admittedly, I hadn’t always understood or appreciated the inherent interdependence between people and bees. In fact, I was terrified of them as a boy. But what was once an irrational fear of bees has since transformed into an existential fear for bees—and, by extension, for the ecologies we all share. And now I wonder: if we look closer at our relationships with these magnificent pollinators, what might we learn about our responsibilities to all other-than-human beings?

To help imagine new ways to address our unfolding ecological crises, Telling of the Bees explores the ethical and ecological relationships between people and bees. More specifically, this evolving body of work considers the opportunities and implications of these interspecies interactions as they manifest across industry, agriculture, ecological research, environmental conservation, human healthcare, bioengineering, and spirituality.

Download project PDF

To consider

What are our environmental and ethical responsibilities to bees? And what are their responsibilities to—and because of—us?

apitherapy

ā-pi-ˈther-ə-pē

the use of substances produced by honeybees (such as venom, propolis, or honey) to treat various medical conditions in humans

the use of substances produced by honeybees (such as venom, propolis, or honey) to treat various medical conditions in humans

A patient looks on as her therapist works to secure a honey bee during an apitherapy treatment. In Bee Venom Therapy (BVT), the patient is injected with apitoxin (bee venom), through live bee stings or lab-extracted solutions delivered by syringe. All methods of venom extraction are lethal to the bee. Bellaire, TX. 2019

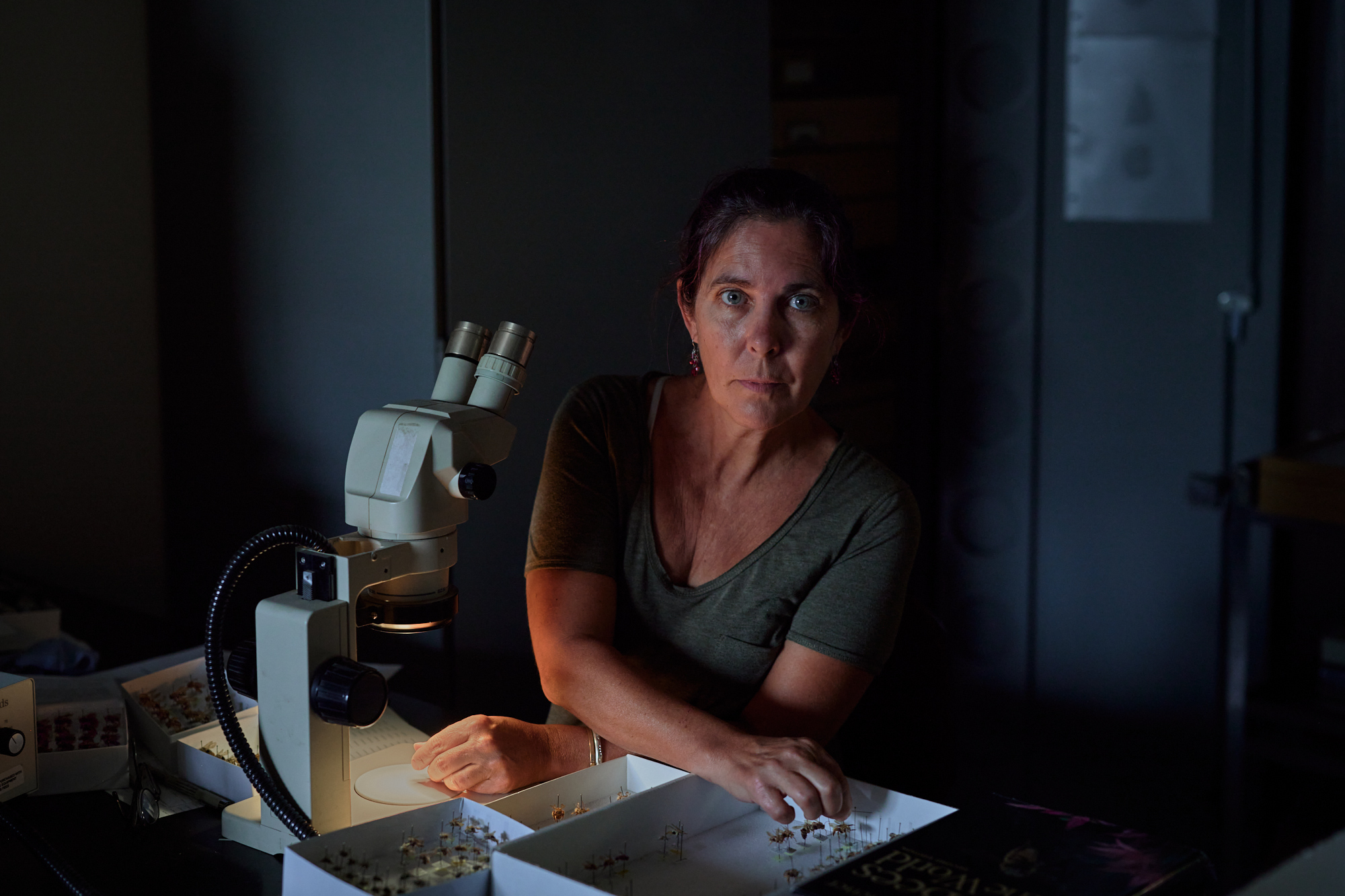

An apitherapist uses tweezers to harvest the

stinger from an uncooperative honey bee during a Bee Venom Therapy (BVT)

session. As stingers are attached to the honeybee's vital internal organs, all

methods of venom extraction are lethal to the bee, which is eviscerated

(disemboweled) alive during the process. Bellaire, TX, 2019

An apitherapist uses tweezers to harvest the

stinger from an uncooperative honey bee during a Bee Venom Therapy (BVT)

session. As stingers are attached to the honeybee's vital internal organs, all

methods of venom extraction are lethal to the bee, which is eviscerated

(disemboweled) alive during the process. Bellaire, TX, 2019

Telling the bees, an etymology

Across cultures, it was once common for people to inform

their beehives of important developments in the household, including births, marriages, and deaths. Named in

honor of this tradition, this body of work considers how

we now choose to live with, alongside, and through bees.

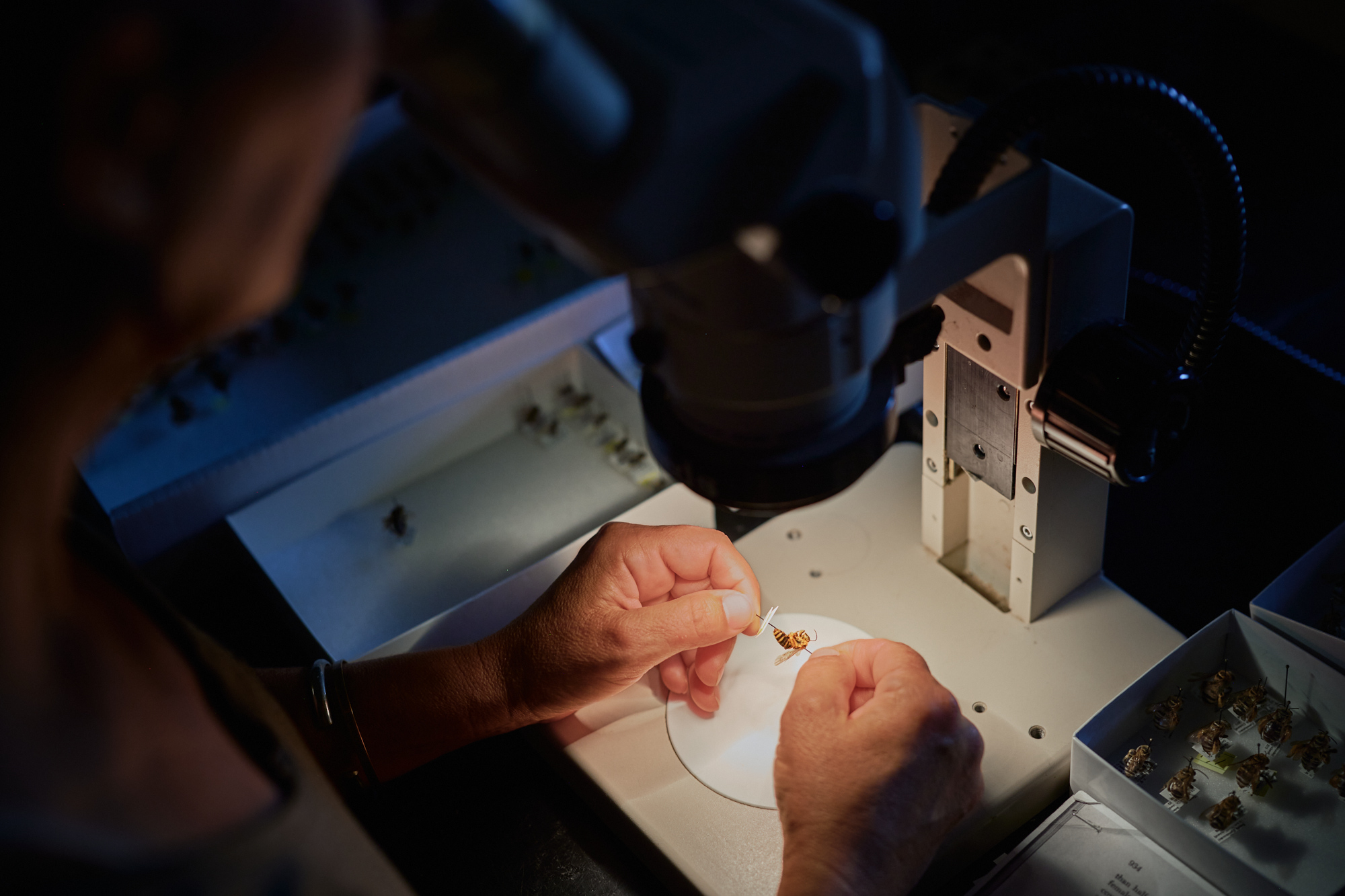

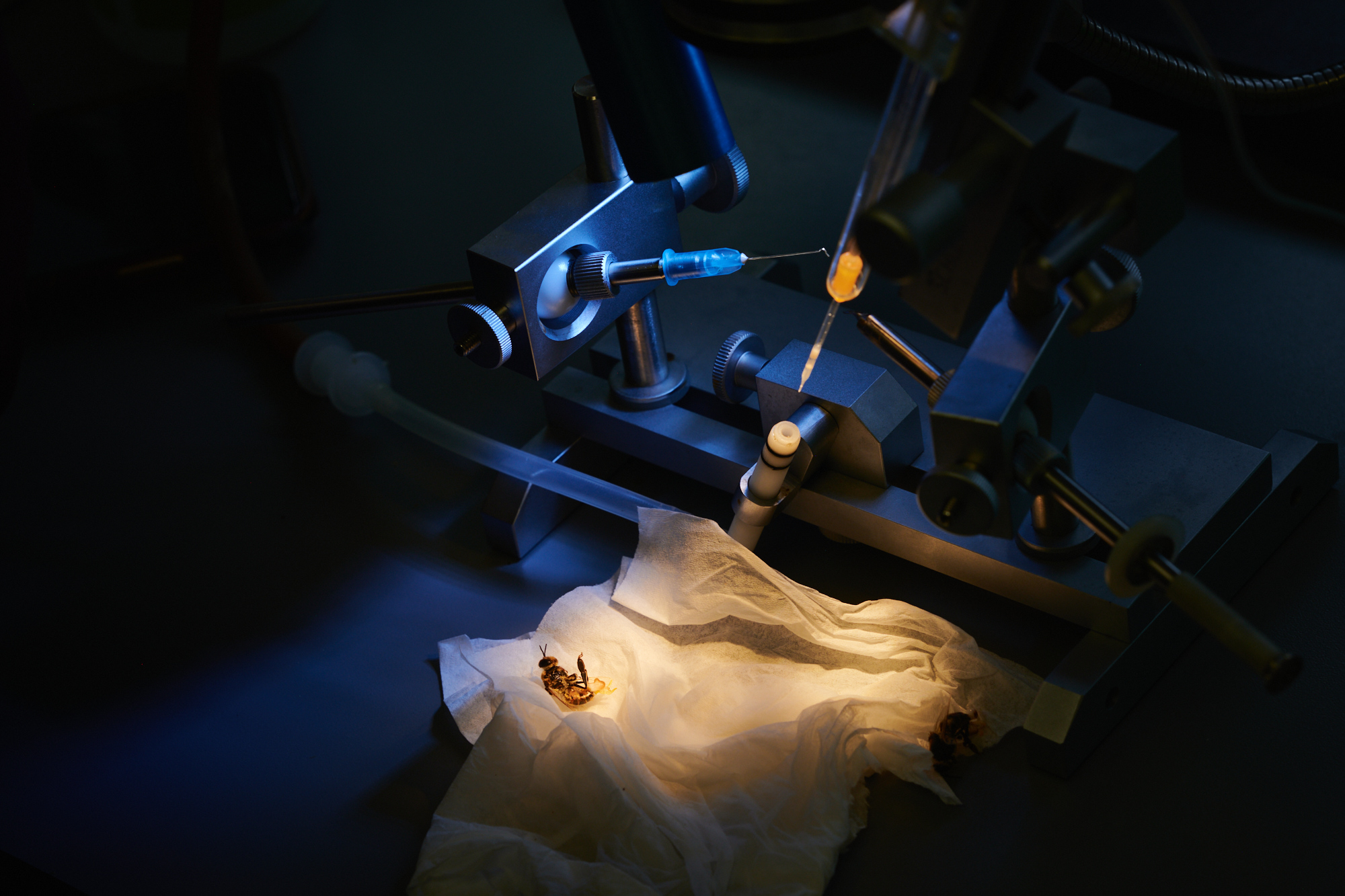

A dead drone lies beneath the apparatus used to

harvest his semen for a genetic experiment at the Honey Bee Lab at Texas

A&M University. In order to extract semen from a drone, researchers “pop”

him by crushing his thorax between the thumb and pointer finger to forcefully

expel his genitals from his abdomen. His semen is then collected using a

pipette. After harvesting semen from multiple drones, the same device is used

to anesthetize and artificially inseminate queens. In addition to being a

standard practice for genetic research in honey bees—as is the case here—this

process is also used to commercially breed queens for beekeepers seeking hives

with specific genetic traits and behavioral characteristics. College Station, TX, 2021

A dead drone lies beneath the apparatus used to

harvest his semen for a genetic experiment at the Honey Bee Lab at Texas

A&M University. In order to extract semen from a drone, researchers “pop”

him by crushing his thorax between the thumb and pointer finger to forcefully

expel his genitals from his abdomen. His semen is then collected using a

pipette. After harvesting semen from multiple drones, the same device is used

to anesthetize and artificially inseminate queens. In addition to being a

standard practice for genetic research in honey bees—as is the case here—this

process is also used to commercially breed queens for beekeepers seeking hives

with specific genetic traits and behavioral characteristics. College Station, TX, 2021